As far as I know, the coconut does not form part of the offerings made to god or gods in Meitei rituals and ceremonies that are thought to be uninfluenced or uninfluenced by Hinduism; for example, Cheiraoba. From our anthropological study of the world's diverse cultures we know that the offerings made, such as fruits, vegetables and animals, are always indigenous. Of course not all indigenous plants and animals find their way into a community's rituals--just a few receives that favor while the rest remain common plants and animals. (What determines this inclusion and inclusion is beyond the purview of this post.) For a fruit or a plant not to have found its way into the rituals of a community at a place does not necessarily mean that that plant or fruit was/is not indigenous to the place. We have to look for other evidences as well.

That being said, it is still intriguing that coconut barged in on the cultural scene all of a sudden at certain point of time in Manipur's political and cultural history. And considering the importance it assumes in most Manipuri rituals beginning at that moment while it did not figure prior to that seems to mean that something critical really happened.

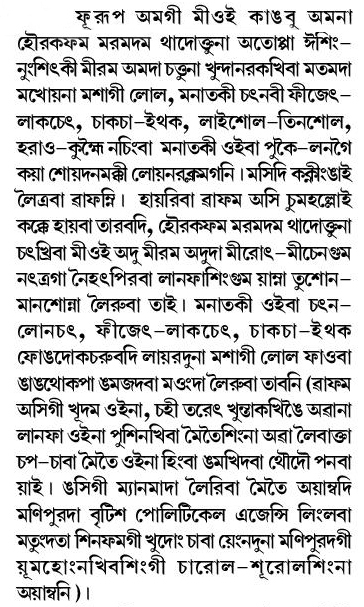

This line of thinking is corroborated by an independent

Manindra Konsam article in the

Sanaleibak (Monday, 11 September 2017) I read two days ago (14 September 2017)--a very closely argued essay possibility of Chakkouba being introduced only relatively recently after groups of Meiteis migrated from Manipur to Bangladesh, Assam and Tripura, as apposed to the traditional received mythical idea that the festival started when Laishna (wife of Nongda Lairen Pakhangba, the purported first king of Manipur in the common era) was invited to a lunch by Poireiton (he was her sister or he sistered her).

This article has critically informed my research into the etymology of the word yubi (coconut). For most of us, yubi always stands in an emotional connection with Chakkouba, and when there is a change in its place on the historical time scale as regards its origin, it can't help changing our perception of the word's history. That is why I consider the Manindra Konsam article is critical and bring it here into our context, with relevant notes. While the article can be followed at the hyperlink above, I have also reproduced it in an image format for convenience. Besides summarizing the key points Manindra makes in the article, I will also reproduce the images of the relevant parts.

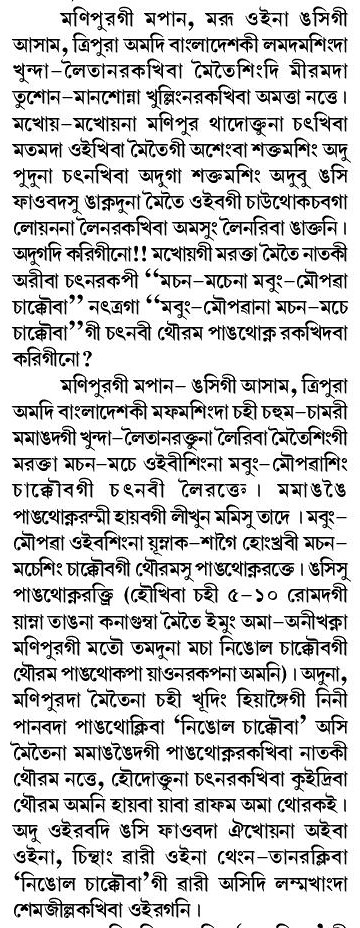

Manindra rightly argues that when a population moves from one place to another, they do not move in a vacuum--they bring their culture with them and practice it wherever they happen to be IF THEY LIVE INDEPENDENTLY WITHOUT ANY SUPPRESSION THAT MAKES PRACTICING CERTAIN OR ALL ELEMENTS OF THE CULTURE IMPOSSIBLE.

We have experiences of both kinds--(i) the Manipuris who migrated to Bangladesh, Assam and Tripura have always lived independently and strongly without any external cultural aggression, while (ii) the Meiteis who were taken as prisoners of war or moved in search of livelihood to Burma have never enjoyed freedom of this kind and they have lost most of their Meiteiness from them because in their oppressive living conditions they do not have the space to practice the culture they have known and came with.

Examining the cultures of the Manipuris in the contiguous states and Bangladesh, Manindra does not find Chakkouba being celebrated in these places, while all other elements in the Manipuri culture are practiced there the way they are done in Manipur. The thus concludes that if it is true that populations necessarily carry their cultures when they move and if nobody is stopping these diaspora Manipuris in diverse places from celebrating Chakkouba, then why don't any of them celebrate this festival particularly, like in unison? It seems to point to the possibility that Chakkouba developed in Manipur only after the Manipuri diaspora had moved in several waves (a quick trip to the history of Manipur to pinpoint the time of the migrations of Meiteis to the contigoous areas would be interesting). One landmark time in history may be the reign of King Chandrakirti, 1850 - 1886, when the direction of the hosting changed from the sister to the brother. This would not have been insignificant and without a reason.

How is Chakkhouba relevant in the etymological study of the word

yubi? Youbi is culturally inseparable from Chakkouba--it is one of the offerings made to god on that day and one of the things sisters bring to their brothers as a gift. Significantly, and as noted above, yubi does not figure in Cheiraoba, which is a far older festival.

The addition of yubi in Lai Haraoba offerings is also a recent one. Old Manipuri texts on Lai Haraoba do not list coconut among the offerings--fruits, vegetables, etc.

Thus it is probable that yubi, which we do not see growing much in Manipur, is a culturally imported plant.

There is still another angle to this. Late last night (it is 03:03 of 16 September now, and it was before the first second of this day, that is in the late hour of 15 September), in one of our regular telephonic conversations these days, Ksh. Sanatomba from Sagolband, brought to my attention the connection between the coconut and the pena. The sound box of the pena. The sound box of the pena is made of the coconut shell. This may pretty easily have one to believe that pena is inextricably associated with the coconut. It is not. The coconut is a tree and its fruit, and the pena is a musical instrument. They cannot be naturally together. There must have been a cultural evolution for the coconut and the earlier models of the instrument or at least the idea of the musical instrument to be brought together. Before the coconut-pena connection, Sanatomba thinks, the pena sound box may have been a gourd shell. He cites the example of the Tangkhul singer and musician Rewben Mashangva's traditional instrument. I have watched Rewben's performances and late last year I watched most of his YouTube videos. As a music hunter of sorts, I have always appreciated this man and his art, and I could immediately connect when Sanatomba referred to his instrument. That is probable--the more durable coconut shell replaced the brittle gourd shell. Nobody before him has made the connection yet. But it is perhaps too obvious to consciously see, as Sanatomba says when I wondered aloud why no Manipuris talked about this if anybody knew--did they fear?

If Sanatomba is right, then it will further make the coconut younger in Manipur's culture. (I will conduct the relevant research and publish the finding soon here.) If this argument holds good, then we have to review certain aspects of our perception of the game, yubi lakpi.

As noted in my earlier post in this thread, yubi is undoubtedly our word, with not identifiable lexical influence from the languages the speakers of the language have had contacts with in the memorable past--Hindi, Sanskrit, Begali, Assami, and Burmese. (I have yet to look into the possible language (or linguistic) links between Manipuri and the languages spoken in the South East Asian countries. That may shed an important light on certain aspects or elements of our Manipuri.)

Thus it begs the question--how did the word 'yubi" develop indigenously if the thing it refers to is not indigenous. That is not a difficult question to answer. There are various ways of words developing indigenously when their referents are not indigenous. But I will write about that in another post/comment.